Tuberculosis, often called the White Plague along with several other infectious diseases, swept through Australia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Something needed to be done to separate the contagious patients from the healthy, so sanatoriums were soon being considered in all of the states. The first one was established in Coolgardie, about 550 km north of Perth, in 1906.

As the focus for treating TB patients was sunshine and fresh air (not closed and isolated hotel rooms where coronavirus ) According to an inhabitant in 1906, the sanatorium was attractive, comfortable, and the patients had every care possible - all paid for by the government! The wards were long and airy, shaded by trees, making them cool on hot days, and there were small gardens. The patients ate well (although the food sounds stodgy) and they were given 'delicious' cups of hot milk when they got up. The sanatorium sounds awful for 'owls', though. The hot milk arrived at 6.00 am! Those who were very sick received extra luxuries, such as roast chicken or custard.

He also praised Dr Mitchell, who was the resident government medical officer and head of the sanatorium. Dr Mitchell eventually became a leading expert on lung diseases. He wrote that Dr Mitchell was 'most patient with the most despondent and nervous'.

The people who lived in the nearby town were, of course, terrified of catching the disease, so, according to another letter, the inhabitants were sadly prevented from leaving the grounds. This deprived them of their daily walks, so they were very upset.

The Coolgardie Sanatorium was replaced by the Wooroloo Sanatorium in 1914.

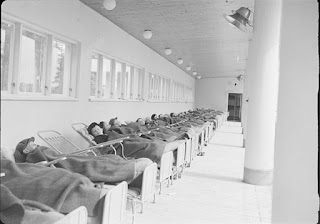

You can see a picture of servicemen convalescing at Wooroloo here.

Children in a Sanatorium Finnish Museum of Photography, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sources

Letter, The West Australian, 20 December, 1906

Letter, The West Australian 23 September, 1908